‘I am a child of the House of Commons.

‘I have lived my life in the House of Commons, having served there for 52 out of the last 54 years of this tumultuous and convulsive century. I have indeed seen all the ups and downs of fate and fortune there, but I have never ceased to love and honour the Mother of Parliaments, the model of the legislative assemblies of so many lands.’

Here Maurice Wiggin, one of the most eminent of this country’s television critics, gives his personal report on Independent Television’s coverage.

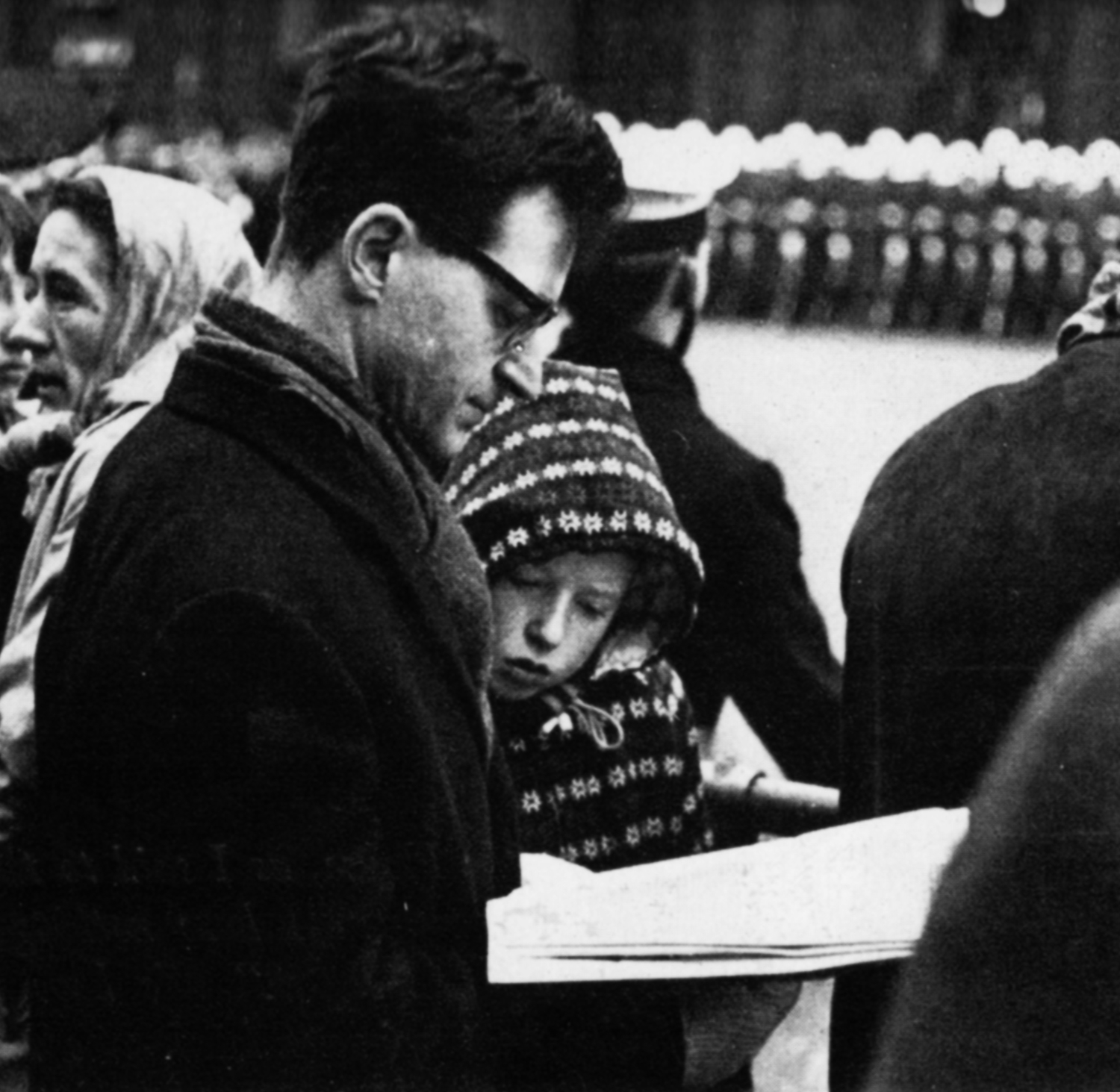

The forecast was wintry. But he was a man who defied wind and weather, and all through the night the people whom he led and loved defied it, camping out cold on the granite and concrete pavements, waiting. At dawn they shook themselves awake and warm, and ate their sandwiches and spruced themselves up as best they could. And now they were reinforced by an infinity of people coming in to the capital. These were people of all nations and ages and many were unborn when he made it possible that they should be born free. But mostly they were his countrymen and countrywomen who remembered and revered him. They came in to the capital under the wintry sky and they thronged and they thickened along the processional route, a multitude. And there at 8.30 on a grey Saturday morning the cameras discovered them.

Forty-five cameras like the multiplex eye of some unimaginable insect. Now for an expectant hour or more this eye of many facets roved the route, and looked at his London; and looking at his London, looked too at his life, who was the greatest Londoner. Over the fretted skylines of Westminster, his home of homes, which stood black against the grey sky, a voice spoke: “Who is the happy warrior, who is he…?” and a voice took up the prologue, “with a sort of wonder.” It said, “He was a great man for pageantry in its place, and this was its place.” It spoke of “the greatest act of public leave-taking.” And expectancy grew. It was a day when there were no individuals, only a people; yet individuals spoke, as the cameras established them, pinpoints of identity within and subserving a larger identity. There was growing now, with the growing expectancy, an unpremeditated picture of his life; his steps and voice ringing again, ghostly echoes, on these stones; and to see this vast organisation of departure and how it came together, tending inexorably towards the moment, this served as a gradual gathering-up of the loose filaments of the spirit, so that when the moment arrived and it was 9.45 a.m. and the prologue was over, why, then, a watcher in his home was detached from self and surroundings and firmly focussed on the act of homage.

Now we grew chronological. Time took over. While he lay in Westminster Hall we still possessed him, in a strange self-deluding yet self-preserving sense. But when the coffin left the catafalque, when the first step was taken on the last journey, then every pace and every moment ticked off was irreplaceable, and the strong sense of finality changed mere sadness into solemnity. So for the watcher the first great moment struck when a camera perceived, emerging from the cavernous shadow of Westminster Hall, the Earl Marshal of England; like a wraith emerging, yet also like a rock. A figure we were to come to know very well, a figure of imperiousness incarnate. And behind him eight tall, bare-headed Grenadiers bearing the flag-draped coffin, each with his cheek laid tenderly against that flag, and a sergeant-major of Inkermann Company, the Second Battalion, going before them with a face of stone.

The ranks of the blue-jackets had opened like a machine, yet not a machine. They laid the coffin on the gun-carriage and the sailors took the strain. The family mourners fell in behind, civilians in sombrest black, Mr. Randolph Churchill with his son Winston at his side leading the little file, and the black town carriages followed with the ladies of the family, and as the procession moved away a gun was fired in St. James’s Park, the first of 90 minute guns that were to span a lifetime, and the ceremonial of a lifetime. A gun shot that reverberated with the voice of doom. Now it was afoot. At 65 paces to the minute, the slow march of emperors that measures off the last public moments of the greatest. Paces buoyed up and orchestrated on the deep swelling funeral music of the bands. And this is the inner genius of ceremonial, that as time and distance are measured off, sternly diminishing with each slow pace and note, so then, by the alchemy of ritual developed over ages of holding mortality at bay, so grows in all who partake an increasing fullness of pride in the life they shared, an increasing awareness of identity with the valiant dead. And this which is within us grows, as that which is without us diminishes, until at the emptiest moment, when time and distance are consumed, we are most full.

‘On the night of the 10th of May, 1940, I acquired the chief power in the State… I was conscious of a profound sense of relief. At last I had the authority to give directions over the whole scene. I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this trial.’

Now it was permissible, and right, after the procession had fairly begun, for the camera eyes to leapfrog along the route, and this they did. For none can bear to march behind the bier save those who must. And here the particular genius of television entered and made us free. As the blue-jackets moved up Whitehall, we saw them from above, a pattern of white caps seen from above, white round blobs, those funny round white caps that sailors wear. And of course they were not funny at all. There was something almost surrealistic in this view, which the pigeons that went wheeling on the thin cold air had too: a formalised pattern of points of light, two rectangles and in between them the oblong draped with the union flag, and the insignia of the Garter lying on it. Somehow this pattern, moving on up Whitehall, relieved the tension that was growing in the watcher, and by making him for the moment more remote, like a bird, enlarged his comprehension as it changed his perspective. This was true many times in the hour to come, when cameras vertiginous and triumphant looked down from London’s high places, perched in eyries atop the canyon cliffs of this tall town, and showed us spread out below the huge dimensions of this act. These shifts of focus, like a change of rhythm, both rested and enlarged the watcher. And so did the subtle changes of voice and prose when, here and there along the route, at such moments and places as were most apt for it, the commentator paused in his particularity and other voices took over, the splendid voices of Sir Laurence Olivier and Paul Scofield, and the unforgettable voice of Churchill himself, speaking his own words. These historic echoes made a counterpoint to the commentary which deepened the sense of being present at a culmination of human aspiration and achievement which was already taking on, both here and now, the mysterious dimension of myth and legend. This was the fruit of planning and organisation. This was what is meant by creativeness in television. This it was that helped to turn an “actuality” into a work of art. And yet… Not this alone. Life which is the flesh on which art feeds, life which is unpredictable and unpremeditated — living moments of pride and poignancy, details that could only have been half-expected and that etched themselves into the remembering heart… these were the vibrant stuff of the occasion. Details which television selected and isolated and magnified, so that a watcher wherever he might be was made a mourner, miraculously present at every point along the processional route.

Of such moments each would hoard his memories. Perhaps of the six brave Group Captains passing St. Clement Danes, doing the slow march not as parade ground soldiers do it, a little uneasily, hands unmoving, and utterly unpretentious in the modest uniform of the Royal Air Force. The living symbol of The Few of whom he spoke.

Or, perhaps, the most moving moment since the first gun tolled; it was at St. Paul’s. None who saw it will forget it in a hurry. We saw the pall bearers come out of the cathedral. (Leap-frogging ahead, we had seen the great arriving, the Lord Mayor with the Sword of Mourning escorting the Queen and her husband and son through the great doors, we had seen the Archbishop greeting the powerful and prestigious, we had seen what we had certainly never seen before, the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster sitting among the Protestants of 60 denominations; we had seen the captains and the kings arriving, and we had also seen how the great basilica at once imposed upon them, high and low, the common human status of mourners). Now we saw the pall bearers emerge.

They were men of history, and they had been close to him in historic times. Their names were a roll-call. Field Marshal the Earl of Alexander of Tunis. Field Marshal the Viscount Slim. Marshal of the Royal Air Force Lord Portal. Admiral of the Fleet the Earl Mount-batten of Burma. Field Marshal Sir Gerald Templer, Lord Bridges and Lord Ismay. The Earl of Avon and Earl Attlee. Sir Robert Menzies and Mr. Harold Macmillan. They came down the steps, and Lord Attlee tottered and one winced, he was so frail and small. Lord Avon looked anxiously, and a tall officer of the Guards put out a helpful hand.

Then suddenly the coffin was there, and the family grouped like any other family in bereavement, waiting for it to go up into the church. Lady Churchill’s black veil could not quite hide the ravages of grief; but she was erect and indomitable and proud. Then once again the Grenadiers took up the coffin; how tenderly they took it up. And they mounted those difficult steps, the coffin swaying a little, and it was frightening. But finally it went in through the great doors. And the choir sang, “I am the Resurrection and the Life.” Though there were people present from many nations, it was overwhelmingly a British congregation, middle-aged or older than middle-aged, and it was a service of unashamed patriotism in which we took part. It was Churchillian. They prayed, and some of us prayed with them, to Saint George, and the hymns were as Churchillian as hymns could be, which doubtless arose from their being chosen by himself. There was a glory in these songs. One watcher at least felt for the moment that though solemnity was ever-present, sadness was put away.

They were the great joyful hymns on which we were brought up. “Who would true valour see, let him come hither.” The battle hymn of the Republic of which he was a more than honorary son — “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.” “Fight the good fight with all thy might.” And finally, “O God our help in ages past.” Triumph, joy and courage, thanksgiving and a lightness of heart that seemed not incongruous — these were the feelings now of one who watched, with the millions of other outsiders who were made insiders for the day. The trumpeters etched dark against the fret of the dome sounded the Last Post and the cavalry Reveille. The camera eye turned again to the waiting coffin, flanked by great black candlesticks, with his honours and decorations laid out on velvet trays at its head. Then it was time to go. And though we had been buoyed up within, now the clutch of time strengthened its hold again; time that was running out. The Grenadiers performed their service once more (and every time they carried the coffin, one thought, “now there is one time fewer”). The Queen and her husband watched as the blue-jackets took the strain again. The camera looked down a last time from the dizzy dome. And the last march had started.

Perhaps — every watcher will have his own treasured recollection — perhaps it was at Tower Pier that the emotional pressure and poignancy became most nearly too much. Yet perhaps, again, it was as much pride as poignancy. For here, it seemed, was the ultimate distillation of Churchill; of the legendary ambience. The water did it. He was not a spare-time sailor, like Belloc who so admired him, like so many of his countrymen: but he was greatly a man of the sea and a lover of ships. Two banners had followed his coffin through the streets; we had seen them a dozen times. One was the banner of Spencer-Churchill, the other belonged to the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. It was a title he made seem real. Now the pipes were skirling, and as the Guardsmen carried him aboard, bosuns’ whistles shrilled.

It was just an everyday working launch of the Port of London Authority, the Havengore. This too seemed fitting. They laid the coffin on the after-deck. The Norman keep fell away and Tower Bridge loomed up as she stemmed the tide and turned. Then something happened as unpremeditated and spontaneous and touching as Raleigh’s cloak. Nothing in the meticulous organisation of the day was able to over-top this gesture, in simplicity or sincerity or surprise. As Havengore and her attendant launches took station and moved upstream, the great black jibs of the cranes across the river dipped like pennants in salute. And the sun broke through.

So he went up on the last of the flood, under the bridges, and came alongside at Festival Pier. Fighters of the Royal Air Force shrieked across the inverted great bowl of sky. The guns of the Tower boomed their unprecedented 19-gun salute. Not since Nelson had an Englishman been borne to glory on London River. A band played “Rule, Britannia,” jaunty and gay and proud as Punch. The Lord Warden, the Elder Brother of Trinity House who was elder brother to a nation, the soldier who had been First Lord of the Admiralty when it was most needful that he should, Sir Winston Churchill came to shore. There were bosuns’ whistles shrilling again at Festival Pier.

“And the trumpets sounded for him on the other side.”

At this point, then, ended the State Funeral of Sir Winston Churchill. For the last time the Grenadiers took him up tenderly, and for the first time the Earl Marshal of England stood aside, at the salute, and let him pass. From that moment it was a private family funeral. Yet we had not quite said Goodbye. First came the brief moment of the motor car. They put the coffin into an ordinary hearse, and the private mourners followed in ordinary black motors, and they drove the few hundred yards to the sailors’ station, Waterloo. It was an unprepossessing little route: cracked concrete underneath, and hoardings. But everything this day was touched with dignity. Then on to Platform 11, whence trains depart for the sea coast of England. A train was waiting, hauled by an engine called Winston Churchill. It was of the Battle of Britain class. Lord Dowding had named it for him, the old chief of Fighter Command. How long the old man lived, how soon machines are out of date. Though in memory the Battle of Britain is yesterday, the old engine, already superannuated, had had to be brought out of its retirement in the West Country. It was battered and dented, but they had polished it in his honour until it gleamed, and the crest of Spencer-Churchill shone, like his immortal name, on its panting flank. Behind was a funeral coach, and into this they took the coffin. The bearer party was made up of men of the Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars, an amalgamation of the 8th and his very own 4th Hussars, in which he started his soldiering. We saw how the tall men had to duck to get through the door. Then the family went aboard the train, the guard gave a soundless signal, and the engine Winston Churchill breathed deeply and pulled its passengers away, the dead and the living, the mortal and the immortal. We watched it diminish down the line. It looked like the tail-end of any train, going out trumpeting into the suburbs, and then the fields; rolling through the countryside where women waited in headscarves and men paused from their work to see it pass. In two hours it would stop at Handborough and deliver up the valiant man to his last resting place by the village church of Bladon. But we should see no more of that last journey. The train vanished, as the commentator spoke the words that are inscribed on John Churchill’s memorial, and will fit his great descendant too:

“…when exerted the most

Rescued the Empire from desolation

Asserted and confirmed the liberties of

Europe.”

The watcher had been present, wherever he was, through the miracle of television, that transformed actuality into art.

It was television’s finest hour, too.

‘In my long political experience, I had held most of the great offices of State, but I readily admit that the post which had now fallen to me was the one I liked the best. Power, for the sake of lording it over fellow creatures or adding to personal pomp, is rightly judged base. But power in a national crisis when a man believes he knows what orders should be given, is a blessing.’