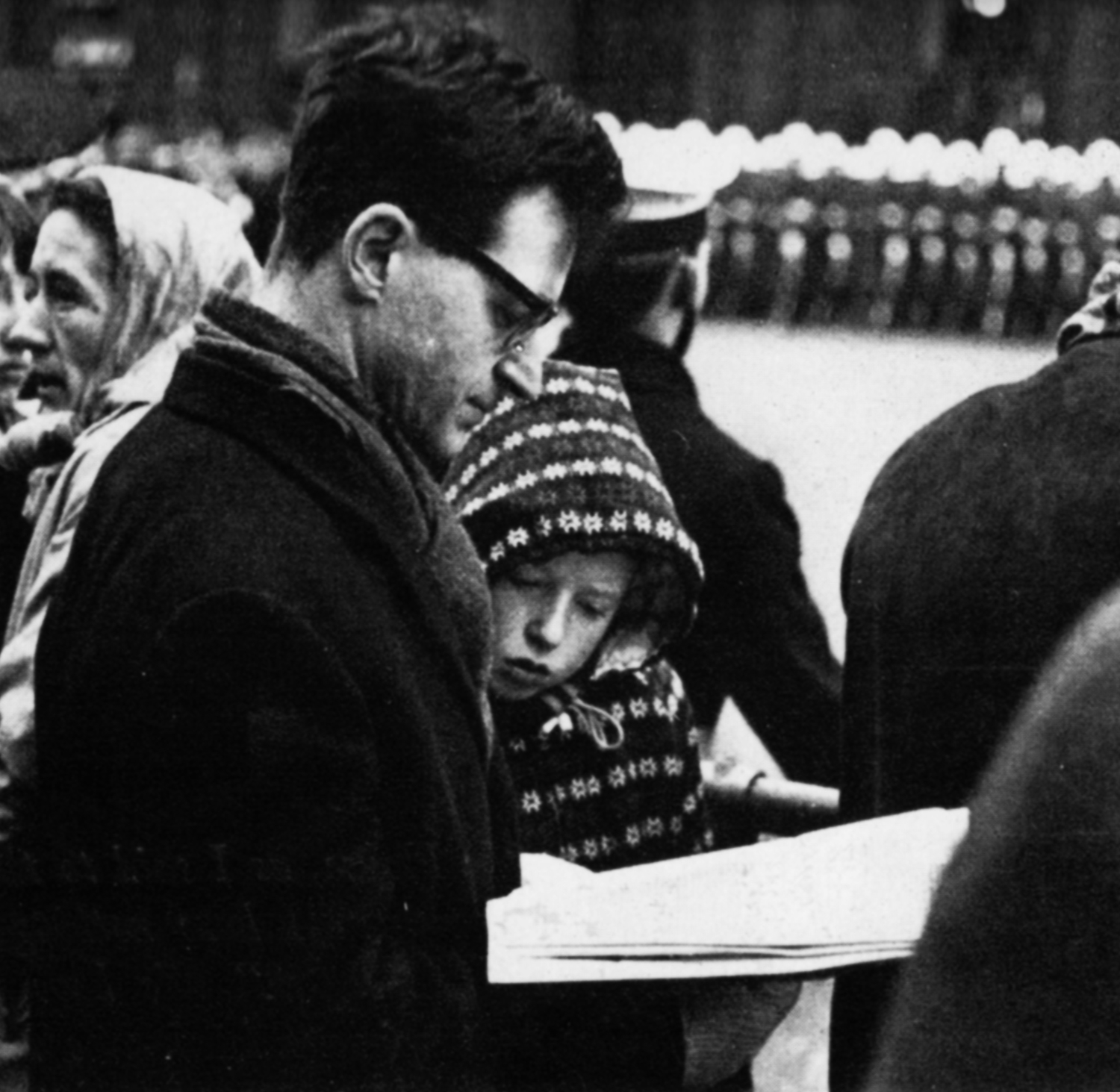

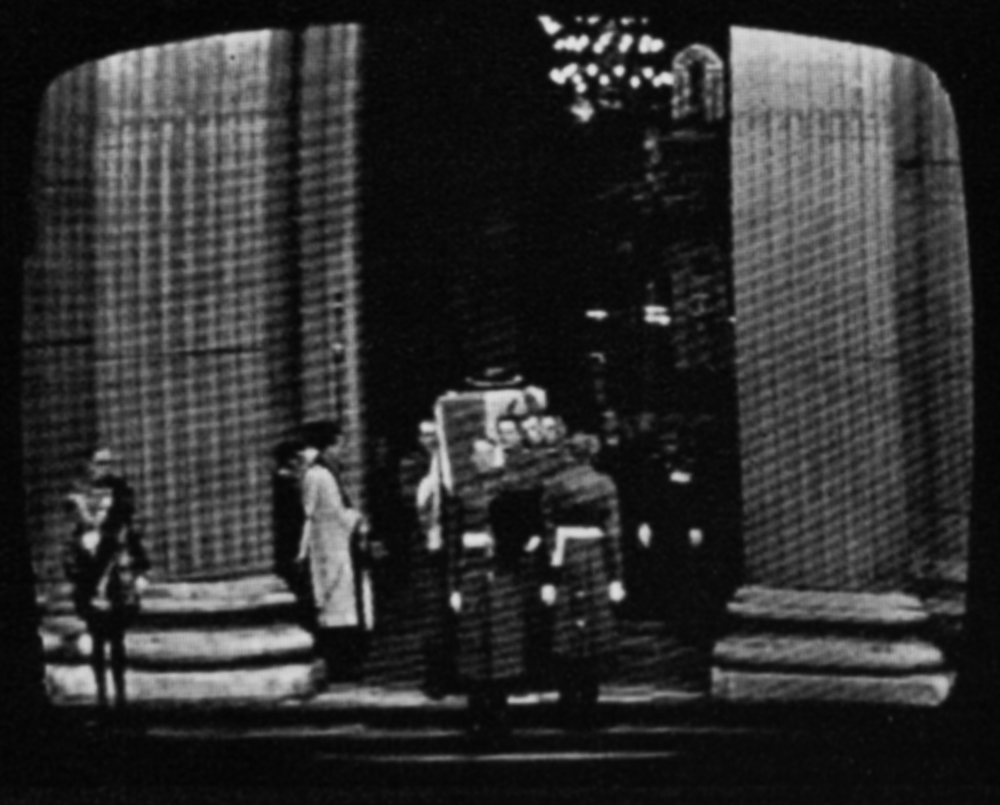

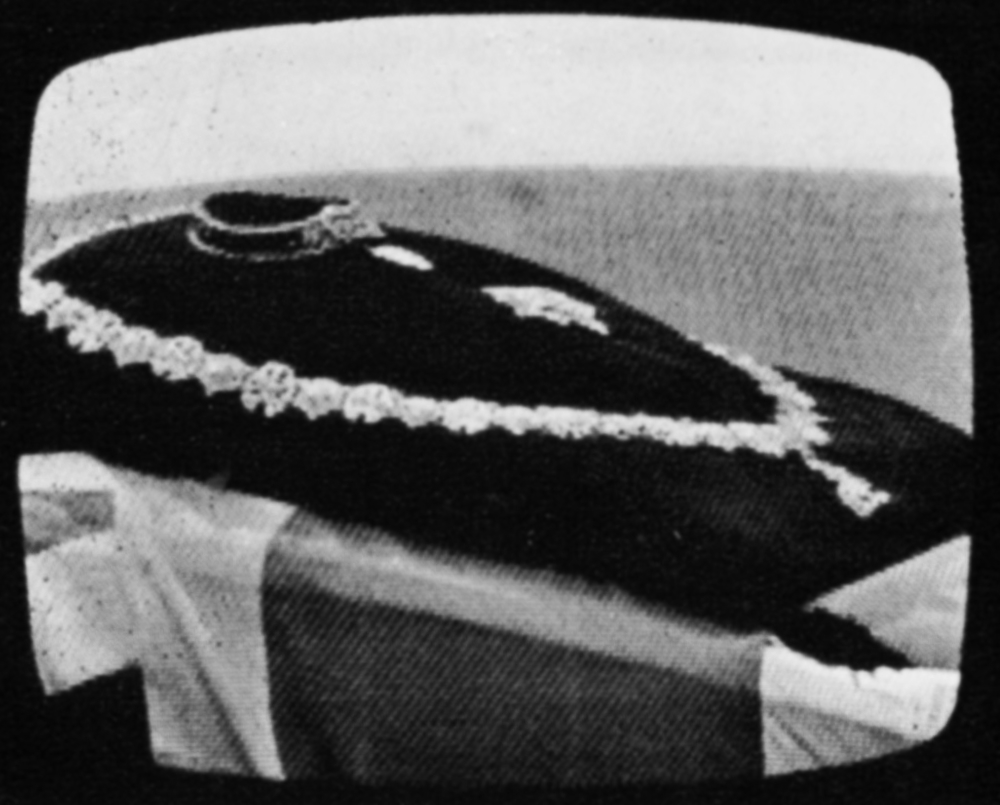

They were the great joyful hymns on which we were brought up. “Who would true valour see, let him come hither.” The battle hymn of the Republic of which he was a more than honorary son — “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.” “Fight the good fight with all thy might.” And finally, “O God our help in ages past.” Triumph, joy and courage, thanksgiving and a lightness of heart that seemed not incongruous — these were the feelings now of one who watched, with the millions of other outsiders who were made insiders for the day. The trumpeters etched dark against the fret of the dome sounded the Last Post and the cavalry Reveille. The camera eye turned again to the waiting coffin, flanked by great black candlesticks, with his honours and decorations laid out on velvet trays at its head. Then it was time to go. And though we had been buoyed up within, now the clutch of time strengthened its hold again; time that was running out. The Grenadiers performed their service once more (and every time they carried the coffin, one thought, “now there is one time fewer”). The Queen and her husband watched as the blue-jackets took the strain again. The camera looked down a last time from the dizzy dome. And the last march had started.

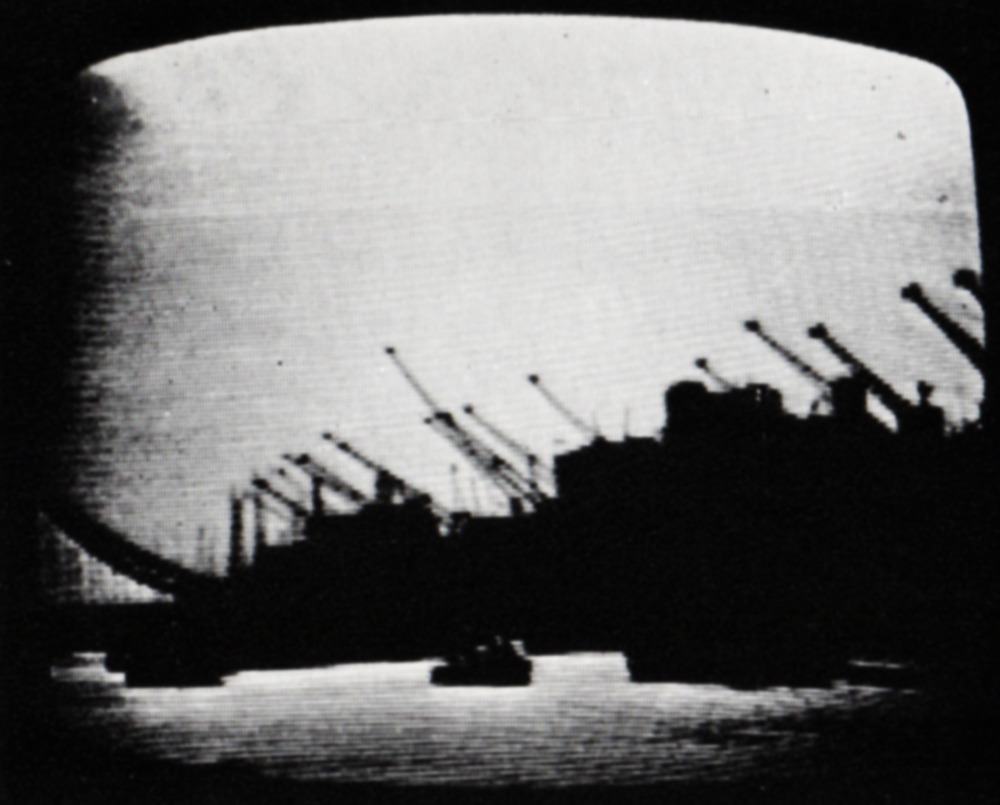

Perhaps — every watcher will have his own treasured recollection — perhaps it was at Tower Pier that the emotional pressure and poignancy became most nearly too much. Yet perhaps, again, it was as much pride as poignancy. For here, it seemed, was the ultimate distillation of Churchill; of the legendary ambience. The water did it. He was not a spare-time sailor, like Belloc who so admired him, like so many of his countrymen: but he was greatly a man of the sea and a lover of ships. Two banners had followed his coffin through the streets; we had seen them a dozen times. One was the banner of Spencer-Churchill, the other belonged to the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. It was a title he made seem real. Now the pipes were skirling, and as the Guardsmen carried him aboard, bosuns’ whistles shrilled.

It was just an everyday working launch of the Port of London Authority, the Havengore. This too seemed fitting. They laid the coffin on the after-deck. The Norman keep fell away and Tower Bridge loomed up as she stemmed the tide and turned. Then something happened as unpremeditated and spontaneous and touching as Raleigh’s cloak. Nothing in the meticulous organisation of the day was able to over-top this gesture, in simplicity or sincerity or surprise. As Havengore and her attendant launches took station and moved upstream, the great black jibs of the cranes across the river dipped like pennants in salute. And the sun broke through.

So he went up on the last of the flood, under the bridges, and came alongside at Festival Pier. Fighters of the Royal Air Force shrieked across the inverted great bowl of sky. The guns of the Tower boomed their unprecedented 19-gun salute. Not since Nelson had an Englishman been borne to glory on London River. A band played “Rule, Britannia,” jaunty and gay and proud as Punch. The Lord Warden, the Elder Brother of Trinity House who was elder brother to a nation, the soldier who had been First Lord of the Admiralty when it was most needful that he should, Sir Winston Churchill came to shore. There were bosuns’ whistles shrilling again at Festival Pier.

“And the trumpets sounded for him on the other side.”

At this point, then, ended the State Funeral of Sir Winston Churchill. For the last time the Grenadiers took him up tenderly, and for the first time the Earl Marshal of England stood aside, at the salute, and let him pass. From that moment it was a private family funeral. Yet we had not quite said Goodbye. First came the brief moment of the motor car. They put the coffin into an ordinary hearse, and the private mourners followed in ordinary black motors, and they drove the few hundred yards to the sailors’ station, Waterloo. It was an unprepossessing little route: cracked concrete underneath, and hoardings. But everything this day was touched with dignity. Then on to Platform 11, whence trains depart for the sea coast of England. A train was waiting, hauled by an engine called Winston Churchill. It was of the Battle of Britain class. Lord Dowding had named it for him, the old chief of Fighter Command. How long the old man lived, how soon machines are out of date. Though in memory the Battle of Britain is yesterday, the old engine, already superannuated, had had to be brought out of its retirement in the West Country. It was battered and dented, but they had polished it in his honour until it gleamed, and the crest of Spencer-Churchill shone, like his immortal name, on its panting flank. Behind was a funeral coach, and into this they took the coffin. The bearer party was made up of men of the Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars, an amalgamation of the 8th and his very own 4th Hussars, in which he started his soldiering. We saw how the tall men had to duck to get through the door. Then the family went aboard the train, the guard gave a soundless signal, and the engine Winston Churchill breathed deeply and pulled its passengers away, the dead and the living, the mortal and the immortal. We watched it diminish down the line. It looked like the tail-end of any train, going out trumpeting into the suburbs, and then the fields; rolling through the countryside where women waited in headscarves and men paused from their work to see it pass. In two hours it would stop at Handborough and deliver up the valiant man to his last resting place by the village church of Bladon. But we should see no more of that last journey. The train vanished, as the commentator spoke the words that are inscribed on John Churchill’s memorial, and will fit his great descendant too:

“…when exerted the most

Rescued the Empire from desolation

Asserted and confirmed the liberties of

Europe.”

The watcher had been present, wherever he was, through the miracle of television, that transformed actuality into art.

It was television’s finest hour, too.